Rich Adin has an interesting post about e-book pricing over on The Digital Reader blog. In “Valuing E-books: Is It a Sensory Problem?”, he compares e-books to things like Starbucks coffee and movies, which we are willing to pay premium prices for, and wonders why the same isn’t true of e-books. His conclusion? E-books lack the sensory components that even a print book has.

It’s an interesting and valid theory, and it made me re-evaluate my position on e-book pricing, at least somewhat. Two things he didn’t address, however, complicate his theory.

First, Adin points out that people are willing to pay twice as much for Starbucks coffee as, say, McDonald’s coffee, and he’s right. That’s partly due to the perceived value (really delicious coffee, made exactly the way you want it) and partly due to the cachet (Starbucks is the “in” place to get coffee.) The world of e-books isn’t really equivalent. Amazon and Apple are both trying to position their readers — Kindle and the iPad respectively — in the “in” gadget category when it comes to e-readers, but e-books themselves don’t have an “in” cachet to them yet. When it comes to books, “in”-ness is more related to content than media . It’s not about whether you read the latest Dan Brown novel in print or e-book format. It’s about whether you read it at all.

Second, when Aden compares e-books to movies, he’s missing something. E-books are, as he points out, an ephemeral experience in some ways. You see a movie, then it’s over. You read a book, then it’s over. It’s true that in either case, you can go back and do it again. Movie fans, like avid readers, often revisit old favorites, and they’ll pay for a copy that allows them to do that. So Aden’s comparison between movies and e-books seems reasonable — at first glance.

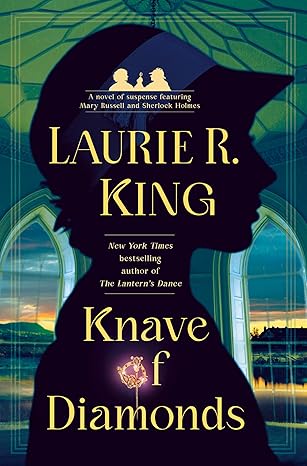

The problem isn’t that people are willing to pay more (or more willing to pay) for a movie than for an e-book. The problem is that readers are are comparing the cost of e-books to the cost of printed books. That’s a very reasonable comparison to make. I did a little checking online. The Kindle, Kobo, and MacMillan e-book versions of Laurie R. King’s The Beekeeper’s Apprentice sell for $9.99. For 51 cents more, Amazon will sell you the physical book in trade paperback (which retails at MacMillan for $14.00), or you can find a used copy at a used bookstore for around $4.00. Or how about this: a brand-new paperback romance, mystery, or thriller retails for around $7.99 in either e-book or print form. However, many retails discount the bound copies of paperback best-sellers or expected best-sellers, bringing the price lower than that of the e-book — sometimes as low as $5.99.

When a reader sees prices that are either the same (or nearly the same) or even higher for an e-book, and then compares what they get for their money, the physical, printed book wins out. Why? The physical book has some distinct advantages. First, you can lend, give away, or resell a printed book, but not an e-book — so the e-book’s overall value is, in reality, less than that of the bound version. Second, a printed book will last as long as the paper and binding do, and it will be readable at any point during its lifetime. The e-book, on the other hand, is only readable as long as the device for which it was purchased lasts. If you buy a book for the Kindle, then replace that Kindle with a Sony or a Nook, that book is effectively gone from your collection. If you buy ePub books, there’s still a problem — the DRM authorization usually only covers the device(s) for which you purchased the book.

In my humble opinion, it’s these comparisons that make many consumers ware of purchasing e-books. Especially those of us who can remember cassette tapes — let alone 8-tracks.