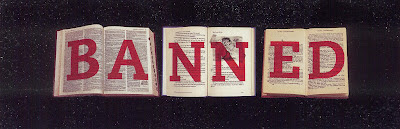

This week, September 30 to October 6, marks the 30th Banned Books Week, “an annual event celebrating the freedom to read.” * The list of books that have been challenged or banned from schools and public libraries over the last 30 years includes some of the very books often taught in school, including Huckleberry Finn, Catcher in the Rye, To Kill a Mockingbird, and The Color Purple, as well as popular children’s books such as the Harry Potter and Captain Underpants series.

Determining which books a school or public library should or may carry (or teach, or let students read) is a tricky issue. We have always restricted some books, at least, from children’s and teens’ sections and school libraries; the type of material restricted tends to be determined by societal norms: in other words, by society as a whole. We still do this, although our ideas of what is appropriate for children have changed over the decades. Some things remain pretty constant. I don’t think there are many people who would disagree that some material is simply not suitable for children — explicit pornography, for instance.

The problem arises when an individual or a few people seek to impose their own standards, as opposed to a widely-held societal standard, on an entire and potentially diverse school, district, or community. The Harry Potter books were challenged by deeply conservative Christians opposed to books about “witchcraft” and magic, despite the fact that many (in most places, a majority) of parents — often Christian themselves — had no objection to the books, and in some cases probably appreciated the effect the books had on their children’s interest in reading. (Believe it or not, even traditional fairy tales like Sleeping Beauty or Rapunzel have come under fire for similar reasons — not various retellings, but the stories themselves.) J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings was actually burned in front of a church for being satanic, although the author was in fact Catholic and the overall theme is one of confronting and defeating evil. Tolkien’s books have also been challenged in and banned from some schools and libraries for their “anti-religious” content. (Tolkien himself wrote to C.S. Lewis that LOTR was a “fundamentally religious and Christian work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision.”**)

The problem arises when an individual or a few people seek to impose their own standards, as opposed to a widely-held societal standard, on an entire and potentially diverse school, district, or community. The Harry Potter books were challenged by deeply conservative Christians opposed to books about “witchcraft” and magic, despite the fact that many (in most places, a majority) of parents — often Christian themselves — had no objection to the books, and in some cases probably appreciated the effect the books had on their children’s interest in reading. (Believe it or not, even traditional fairy tales like Sleeping Beauty or Rapunzel have come under fire for similar reasons — not various retellings, but the stories themselves.) J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings was actually burned in front of a church for being satanic, although the author was in fact Catholic and the overall theme is one of confronting and defeating evil. Tolkien’s books have also been challenged in and banned from some schools and libraries for their “anti-religious” content. (Tolkien himself wrote to C.S. Lewis that LOTR was a “fundamentally religious and Christian work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision.”**) Race and racial slurs have been frequently cited as reasons for banning books from middle and high school libraries and curricula. Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird have each been challenged for use of racial epithets (like “nigger”) and their (differing) depictions of race relations — although both are appropriate to the eras in which the novels are set. While I do not underestimate the pain which racial slurs can and do cause to minority students, reading and talking about these books in class offers the opportunity for important discussions on how racial prejudices have and have not changed and how students today experience race — in other words, the opportunity for fostering greater understanding between students of all colors.

Race and racial slurs have been frequently cited as reasons for banning books from middle and high school libraries and curricula. Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird have each been challenged for use of racial epithets (like “nigger”) and their (differing) depictions of race relations — although both are appropriate to the eras in which the novels are set. While I do not underestimate the pain which racial slurs can and do cause to minority students, reading and talking about these books in class offers the opportunity for important discussions on how racial prejudices have and have not changed and how students today experience race — in other words, the opportunity for fostering greater understanding between students of all colors.

Profanity and sexual references are other common complaints about even many classic novels — which leads me to wonder whether the adults challenging these books have ever walked down a public middle- or high-school corridor. Frankly, removing such books from the curriculum (at this level, required reading lists and curricula come under fire at least as often as library holdings) isn’t going to “protect” these older students from encountering both profanity and sexual issues and relationships in their daily lives, both in and out of school. And many of the books challenged on these grounds are classics found on most upper-high-school reading lists; most colleges will expect students to have read at least some of these titles. (You can find a list of the most frequently challenged classics here.)

Almost any book has the potential to offend somebody, somewhere, someday. Animal-rights advocates may be offended by books in which animals are caged, hunted, or raised for food — like Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books or even Curious George. Those opposed to homosexuality will object to sympathetic or positive depictions of it (or even to any reference at all), while those in favor may object to books which use derogatory slang terms. Atheists could (and sometimes do) object to Christian content, even when not explicit (C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, for instance.) My point isn’t that a community should never choose to remove or exclude a book from its libraries and school curricula, but that such decisions should be based on both the values of the community as a whole and the merits and potential benefits of the book in question, rather than on the objections of a few.

* “Banned Books Week: Celebrating the 30th Anniversary of the Freedom to Read.” American Library Association website: http://www.ala.org/advocacy/banned/bannedbooksweek

** “Banned Book Awareness: ‘Lord of the Rings’ by J. R. R. Tolkien.” R. Wolf Baldassaro, Banned Books Awareness website: http://bannedbooks.world.edu/2011/03/13/banned-book-awareness-lord-rings-jrr-tolkien/