The Warlock in Spite of Himself Series: Warlock #1

The Warlock in Spite of Himself Series: Warlock #1 on (originally published 1969 by Ace)

Pages: 283

Add to Goodreads

Rod Gallowglass is a man of science who does not believe in magic. Gramarye is a world of witches and warlocks. Of strange abilities and phenomena. A world where society mirrors Earth's own Middle Ages, and a world headed for doom.

Rod Gallowglass must become a part of the local fabric to save the world from both itself and external forces that threaten its existence. But to do so, he must put aside his own convictions and beliefs, and become a warlock, in spite of himself.

A grand adventure mixing science fiction with elements of fantasy, this is the book that launched a whole series (fourteen books and counting).

Review

I first read The Warlock in Spite of Himself back in high school. I enjoyed it; it offered humor and adventure and a psuedo-medieval setting with soft-SF trimmings. So when I discovered that Christopher Stasheff had re-released it as an ebook, I bought it and happily plunged back in.

I sort of wish I hadn’t.

Warning: Spoilers ahead.

The world of Gramarye is delightful, with its deliberately medieval-European society (the original colonists having apparently been Renaissance Faire and SCA aficionados in all but name). Rod Gallowglass, the protagonist, seems to share the author’s tongue-in-cheek sense of humor; he also possesses a deep loyalty to the ideal of democracy. There are some unusual secondary characters, notably Fess, Rod’s epileptic robot horse, and a dwarf named Brom O’Berin. There’s enough magic to allow for the unexpected and to keep things interesting, and there’s even a love story of sorts.

That’s the good stuff.

What the adolescent me apparently skated over or looked past at the time is the book’s appalling sexism. There are only two female characters of note. One, Catherine the Queen, seems to highhandedly lord it over the men around her, while apparently secretly wishing one of them would simultaneously A) love her, B) keep her safe, D) respect her power and position and E) prove he’s a man (the implication is, by standing up to and even dominating her. Just how he could manage D and E at the same time is unclear.) Stasheff portrays Catherine in one moment as a scared youngster in a lonely and vulnerable position, as a seductress in the next, and a spoiled bitch an instant later. Initially, he tries to justify her somewhat schizophrenic motivations and actions as stemming from her fears and her position, but in the end, he settles for having another character tame her through love and sex. I was reminded of The Taming of the Shrew in its most literal interpretation.

The other female character, Gwendolyn, first seduces the willing Rod before following him, as he has been warned “farm girls” will do. In fact, she’s trying to watch over and protect him, though it takes him a while to catch on. Stasheff tries to imply that Rod loves her from their first encounter but is too misguided to realize it, but he never gives the pair (or the reader) much to base a relationship on. Gwendolyn apparently fixates on Rod almost immediately, and Rod warms up to her as a person (not just a bedmate) once he recognizes her loyalty and protectiveness toward him. Which is OK, I suppose, but Gwen’s role vis-a-vis Rod seems to be limited to a helper, protector, lover, and sex toy, but decidedly not an equal partner or an intellectual equal. What’s interesting is that Gwendolyn’s roles are precisely the ones Catherine appears to want of her suitor. Yet Catherine is depicted negatively as demanding, petulant, overly proud, and high-handed in her rule over her land and her treatment of her suitor. In other words, the woman who serves her man’s needs and stays out of the intellectual discourse (Gwendolyn) is treated sympathetically; the one in power (Catherine) is seen as abusing that power, and must be “schooled” into proper behavior as a ruler and as a woman. Both portrayals are problematic from a feminist standpoint.

It’s ironic that while Stasheff freely admits the ways in which the Cold War mindset heavily influenced the novel, making it now feel quite dated, he doesn’t seem to have even noticed the pervasive sexism in his treatment of the two major female characters. I don’t remember if he handled female characters any better in the later books in the series. I think he did, but given that as a young adult, I glossed over the level of sexism in this novel, I can’t be sure my recollection is correct. Regardless, I’m rather sorry to have tarnished my memory of the book with this discovery. And I doubt I’ll re-read the other books in the series now.

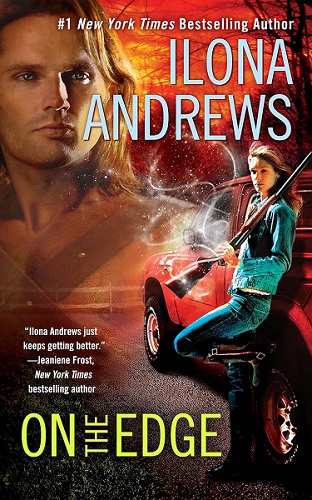

A final note: I have to admit that I much preferred the 1982 paperback cover (below) over the self-published cover (top of post.) I’m sure you can see why! The new cover just doesn’t have the romance (in the medieval sense) of this one — and it’s missing Fess, who is one of my favorite characters.

Rita @ View From My Books

I think the answer to the lack of enjoyment the second time around is that it was originally published in 1969. That was a whole other world than what we live in today, and the author probably projected the norms of society around him into his writing.

I read an article a few months ago (I think I followed a link from your blog) about overt sexism in SF and SFF. It was interesting. Do you remember that one?

Rita @ View From My Books recently posted…Last Round of Photos- @ the Aquarium

Lark_Bookwyrm

You’re certainly right about the author incorporating a lot of the 1960s worldview into his book. What both amuses and appalls me is that in his new foreword, he acknowledges the Cold-War mentality that pervades the book, but doesn’t seem to see the sexism at all.

I should remember the article you’re referring to, but off the top of my head, I’ve forgotten. I’ll have to search through News & Notes to see if I can find it. It might have been on i09, Tor.com, or the Mary Sue…

Katherine @ I Wish I Lived in a Library

Oh I hate when an old favorite doesn’t stand the test of time. I’m kind of funny about sexism in books. For the most part it doesn’t bother me if the book was written in the 60s or earlier if it’s very much on the side. Sometimes it can even come off as funny but if it’s a major part of the story or around a main character it’s so grating.

Katherine @ I Wish I Lived in a Library recently posted…Love Blooms on Main Street – Review and Release Week Blitz

Lark_Bookwyrm

What puzzles me is how I didn’t really pick up on at the time. I mean, I wasn’t completely oblivious to it, but I didn’t realize how bad it was until I reread it. I wonder if part of that is that I remembered the series from the perspective of having read some of the sequels, too. Maybe it’s less egregious in the sequels? But to be honest, I’m not sure I want to reread them to find out!