Rich Adin (An American Editor) has an interesting opinion piece this week in which he suggests that perceived ebook vs. pbook value is largely due to the amount of sensory input each format offers. In other words, consumers see ebooks as being worth less than (hardcover) print books because the ebooks lack the tactile, visual, and even olfactory pleasures of a pbook. Adin gives a desultory nod to issues like the ability to lend or resell the book, but he has come to believe that sensory experience is the key to a book’s perceived value. To use his own metaphor, we value a real rose above a photograph because we can smell it and touch it; it’s sensory (sensual?) qualities make it more valuable despite its brief lifespan.

|

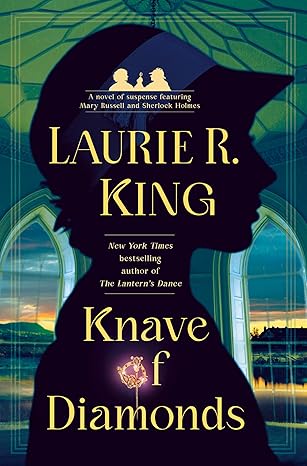

| pbooks vs. ebooks? (photo ©Kara Pekar, 2012) |

It’s an interesting position, and not without merit. Certainly the sensory experience or lack thereof plays some role in the perceived value of pbooks vs. ebooks, but it isn’t the only or even the primary factor. I’ve discussed elsewhere on this blog the issues of longevity (ebooks, because of DRM and formatting, are shorter-lived than pbooks; when the format disappears, so does your ability to read the book) and ownership vs. license (if you buy a pbook, you may resell it, loan it, or give it away; with ebooks, those consumer rights are strictly curtailed or nonexistent, so you really just have a license to the content rather than physical ownership of an object which includes content). I won’t rehash those arguments here, except to point out that both those considerations may affect a consumer’s perception of value to some degree.

Instead, I’d like to look more closely at one of Adin’s supporting arguments. He writes:

Many more ebookers are willing to pirate an ebook – regardless of the rationalization given for doing so — than are willing to steal a pbook from a bookstore. Why is that? If the value is the same, the willingness to pirate/steal should be the same, yet it isn’t. I think it is because ebooks are intangible and thus viewed as of little to no value — ebooks simply do not ignite the same sensory experiences as pbooks.

Adin is missing several points here. First, one very good reason that many otherwise law-abiding people don’t steal pbooks but will pirate an ebook is that they’re a lot more likely to get in trouble for the former. It’s much easier to get caught stealing a physical object from a physical store.

Two, there’s a real difference in how theft or piracy is perceived. Shoplifting (physical stealing) is morally wrong as well as illegal; most people will agree on that. But it’s perfectly legal to rip your the CD you just purchased to MP3 so you can put it on your iPod. Following that reasoning, a consumer might think, “Why should it be wrong to scan a copy of a pbook I bought, so I can put it on my e-reader?” From there it’s a short step to “I don’t have time to scan the pbook I just bought, but I could download the ebook from a torrent site.” Even if the reader is downloading a copy of the ebook without buying the pbook, their reasoning may be that no one is being harmed by their actions — no bookstore is losing a physical copy, and if it’s not a book the reader would have bought in the first place, the author and publisher aren’t losing any money either. In other words, it’s much easier for the person pirating an ebook to morally justify their actions than it would be for them to justify stealing a pbook from a store or library. (Please note: I am not justifying or endorsing piracy, just laying out the reasoning which seem to be behind it, based on comments and posts I’ve read on the Internet.)

There is, in fact, a real difference between piracy and stealing, as well as a perceptual one. Stealing means taking a physical object; the original owner (bookstore or library) doesn’t have it anymore. Piracy means making a copy or copies; it can also refer to acquiring an illegal copy made by someone else. What’s different in recent years is that making copies of books is so much easier. Twenty years ago, people rarely pirated print books; it was so time-consuming and difficult that it wasn’t really worth the trouble. Why spend hours scanning or photocopying and printing out a pbook when you could buy the book for a reasonable amount, or borrow it from the library? People only put in the effort to copy a book when it was really worth it to them; perhaps they couldn’t get a physical copy of the original, or the original was way out of their price range. Ebooks changed the piracy equation. Now, it’s relatively easy to strip the DRM from an ebook and upload it to a torrent site if you have the technical skill, and it’s even easier to download a pirated book from a torrent site and put it on an e-reader. (Of course, people also scan pbooks and turn them into ebooks — usually because an ebook version doesn’t exist, and they want one. It’s a variation on the photocopying of pbooks, and done for similar reasons.)

I’d have to argue, therefore, that the real reasons that people’s “willingness to pirate/steal” isn’t the same between pbooks and ebooks are that a) people are less likely to get in trouble for e-piracy than for stealing pbooks; b) people don’t view piracy with the same level of moral repugnance as they do stealing, for a variety of reasons; and c) ebook piracy is very easy. In other words, ebooks don’t get pirated because people feel they are worth less than pbooks, as Mr. Adin suggests. Ebooks get pirated because e-piracy is an easier, safer, and (to some) morally acceptable way to get the same content as a pbook.

* * *

In his essay, Mr. Adin goes on to talk about the question of content vs. wrapper in valuing a book:

Of course all of this ignores the fact that real value of a book — p or e — lies in the writing, not in its physical structure or presence. Yet when we talk about the value of books, the value of the content is rarely addressed. There is good reason for this. If we were to address the content value, then ebooks and pbooks should be equivalently valued. After all, the word content is the same, only the physical wrapper is different.

Well, yes — or rather, in one case, the consumer gets a physical wrapper, and in another, s/he doesn’t. If you’re going to make that argument, then the dichotomy in the perceived value of pbooks vs. ebooks makes perfect sense. The content is the same, but what is the value of the content as opposed to the wrapper? Publishers have spent decades training the book-buying public that a hardcover is worth more than a trade paperback, which is worth more than a mass-market paperback. Notice that as you go down in price point, you get a less elaborate, less durable wrapper. In other words, the quality of the wrapper goes down along with the price. Furthermore, remaindered books are frequently sold for very low prices, even below mass-market paperback. The obvious conclusion for consumers to have drawn is that the content by itself (including editorial work and cover art) must be worth less than the price of the average mass-market book — less than $7.99, using the current mass-market standard.

Given this conclusion, of course consumers think that ebooks, which have no physical wrapper at all, should cost less than pbooks, even at the mass market level — they expect the ebook price to be more in line with their idea of the content price.*

Publishers are obviously not blind to this perception, since they already price new ebooks below the list price of the same book in hardcover or trade paperback. That only serves to reinforce the belief that part of the price point is dependent on the packaging. And of course, consumers also know that hardcovers in general are overpriced, since so many retailers discount them. I think consumers do understand that they’ll pay more when a book first comes out, even for the ebook, than they will when the book has been out for a year or more; the novelty drives the content portion of the price up a little. (In other words, we “get” that hardcover or trade prices aren’t only about the wrapper –just mostly about the wrapper.) But consumers expect, with good reason, that the ebook price will stay below the current pbook format’s price. This may explain why there is so much resentment over agency pricing.

Perhaps the whole agency pricing thing was in part an attempt to get consumers to match their “content price” concept to the mass-market list price? If so, it didn’t work. First of all, it’s probably impossible to reverse decades of consumer expectations about the relative price of wrappers (packaging) in a few short years. Second, agency pricing only controlled the price of ebooks. Pbooks, even mass-market ones, continued to be discounted by some retailers. If a consumer can buy a pbook (in a physical wrapper) for less than s/he has to pay for an ebook (without a physical wrapper, in which s/he has no resale rights, and which has a much shorter potential shelf life because the format is subject to frequent technological change) — guess which one s/he is likely to buy? And if Walmart sells a $7.99 paperback for $5-something, what does that say to consumers about the overall value — the price point — of the content?

In the end, I’m in partial agreement with Mr. Adin. Certainly, the perceived value of pbooks vs. ebooks is based in part on tangibility vs. intangibility, though not primarily because of the sensory experience, as he suggests. Ownership vs. licensing, the ephemeral nature of ebook formats, the perceived relative cost/worth of the content’s “container”, and even the ease with which the reader can navigate and find information or passages within a book all affect the perceived value of the format in which it is presented.

Unlike Mr. Adin, I don’t think the dichotomy in perceived value is likely to go away. There are valid reasons for consumers to place a lower value on ebooks than on print books. Publishers need to pay attention to those reasons and find a way to price their products which will be perceived as more fair and reasonable. Consumers, meanwhile, need to remember that content is produced by authors, who deserve to be paid (and won’t keep writing and publishing if we don’t support them with our purchases.)

*Ebooks do have a physical wrapper, of course: the e-reader. I don’t think I need to point out that the consumer has already paid a great deal more for that wrapper than s/he would expect to pay for the average book.